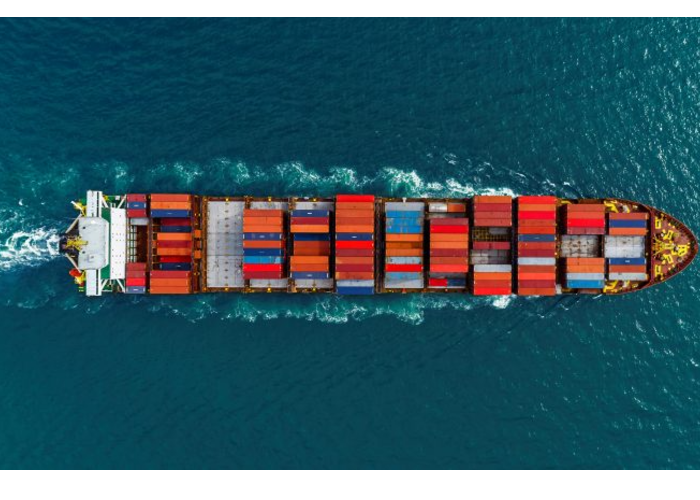

SME’s and consumers are footing the bill for exorbitant freight charges, while transport behemoths benefit handsomely.

Ocean shipping prices are anticipated to remain high far into 2022, ensuring another year of record profits for global freight carriers — but at the expense of smaller businesses and their consumers from Spain to Sri Lanka.

Last year, the spot fee for a 40-foot container from Asia to the United States surpassed $20,000, including surcharges and premiums, up from less than $2,000 only a few years earlier, and was recently hovering around $14,000. Furthermore, due to a lack of container capacity and port congestion, longer-term rates specified in contracts between carriers and shippers are up to 200 percent higher than a year ago, indicating that costs will remain high for the foreseeable future.

Large clients of sea-borne goods, such as Walmart Inc. or Ikea, have the financial clout to negotiate better terms or absorb the additional cost. Smaller importers and exporters, particularly those in developing nations, who rely on carriers to transport everything from electronics and garments to grains and chemicals, are unable to pass on those costs or weather protracted periods of cash flow constraints. The problem has brought attention to shipping companies’ market concentration and their legal exemption from antitrust regulations.

Profits for the Shipping Industry are at an All-Time High

Amruth Raj, managing director of Green Gardens, a vegetable processor situated in rural India, stated, “Small and medium-sized firms are being seriously hit.” When container rates skyrocketed last year, European customers objected at the higher prices, wiping away more than half of his company’s capital. “They take advantage of our despair.”

In the developing world, it’s not just about company survival. On a recent conference call held by the United Nations trade group, Achil Yamen of the Cameroon National Shippers’ Council expressed worry about imbalances in Africa.

“If nothing is done to reverse the trend, the risk of inflation and food security would skyrocket,” Yamen said.

Meanwhile, the backbone of the postwar globalisation march is emerging from the epidemic in the greatest position it has ever had – a dramatic contrast to years of losses in the capital-intensive company. Ocean freight companies are expected to make $150 billion in profits in 2021, a nine-fold increase after a decade of struggling to make any money.

Inflationary Risks and Rising Shipping Costs

The largesse has pricked a raw nerve across the political spectrum, with economists warning that consistently high transportation costs are fuelling inflation and casting a pall over the recovery. High freight costs, which used to fuel mainly brief bouts of inflation, are now becoming a longer-term characteristic of economies in the United States and abroad.

In the past, a 15% rise in transportation costs resulted in a 0.10 percentage point increase in core inflation after one year, according to Nicholas Sly, an economist with the Kansas City Fed. Shipping prices, he noted, are presently a long-term issue rather than a temporary or transient one.

“Those kinds of shocks tend to linger for 12 to 18 months,” Sly explained.

Shippers all across the globe are appealing with authorities to rein in ocean-freight carriers in the face of forces that are upending old business structures. The British International Freight Association fired the next volley on Jan. 5, urging the UK government to look into “distorted market circumstances” in the global container-shipping sector.

The British freight lobby has argued that there has been a concentration of power in recent years. Only ten container lines located in Asia and Europe, led by Maersk, MSC, CMA CGM SA of France, and Cosco Shipping Holdings Co. of China, control about 85% of the capacity for shipping products by sea. Twenty-five years ago, the top twenty corporations controlled about half of world capacity.

Despite the fact that they are nominally rivals, nine of them operate under “alliances” that coordinate timetables and share space aboard ships. Meanwhile, in most major economies, including the European Union and the United States, carriers have long been exempt from antitrust rules.

The Effects of the Pandemic on the Shipping Industry

For the first time, the pandemic proved how skilled carriers have become at regulating the market’s supply of cargo capacity, restricting it when Covid-19 initially jolted the global economy and then ramping it up when demand returned rapidly, sending prices higher than ever. Shippers have grumbled about how the alliances’ monopoly on capacity — ships, timetables, ocean software, and speeds, as well as the millions of steel boxes in circulation — has translated into disproportionate pricing power.

“This market isn’t working for everyone,” said James Hookham, head of the Global Shippers Forum, a trade group that represents importers, exporters, and cargo owners. “We feel this market requires more scrutiny to ensure that those clients are not being taken advantage of.”

Carriers claim the high pricing are an outlier caused by supply and demand mismatches caused by the epidemic, which would naturally settle. The partnerships, according to John Butler, chief executive officer of the World Shipping Council, a trade group representing container lines, are agreements that help the entire system run more efficiently. The council cites higher-than-normal consumer demand in the United States, and Butler attributes many of today’s interruptions to land transportation issues.

“Pre-pandemic, we’ve had lots of capacity, extremely reasonable prices, and plenty of service for the better part of 20 years,” Butler said. “In terms of structural matters, nothing has changed in the industry since then.”

Supply Chain Issues and Port Issues

Supply networks were significantly affected as a result of the soaring demand. Imports were being processed too slowly at major ports in the United States, transportation businesses were running out of drivers, and warehouses were running out of space. Because of port congestion, fully laden ships sat off the coast of California for weeks. Suddenly, a business that had mostly gone undetected by the broader public had become a very visible target.

In September, regulators from the United States, the European Union, and China convened and found that there had been no proof of anti-competitive activity in container shipping thus far. Governments are still on high alert as global supply systems are stretched to their limits.

The White House attacked the industry’s consolidation in November, stating that “this lack of competition leaves American firms at the mercy of only three partnerships” and urging the FMC to “use all of the instruments at its disposal to promote free and fair competition.”

The FMC claims that it has enhanced its surveillance of carrier alliances in order to better track trends and uncover any unlawful activity, such as unfairly restricting supply or failing to compete on price. The government launched an inquiry against Wan Hai Lines Ltd., a Taiwanese carrier, in late December, citing relatively minor infractions of charge regulations controlling container returns. Beyond such measures, even the agency’s head, Daniel Maffei, has stated that there is nothing that regulators can do under present US legislation to prevent broad potential misuse.